Imprisonment in Durham

"Again I was at curst Dunbar,

And was a prisoner taen,

And many weary night and day

In prison I hae lien."

From ‘The Battle of Philiphaugh’, from Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, a collection of Border ballads compiled by Sir Walter Scott 1802-1803

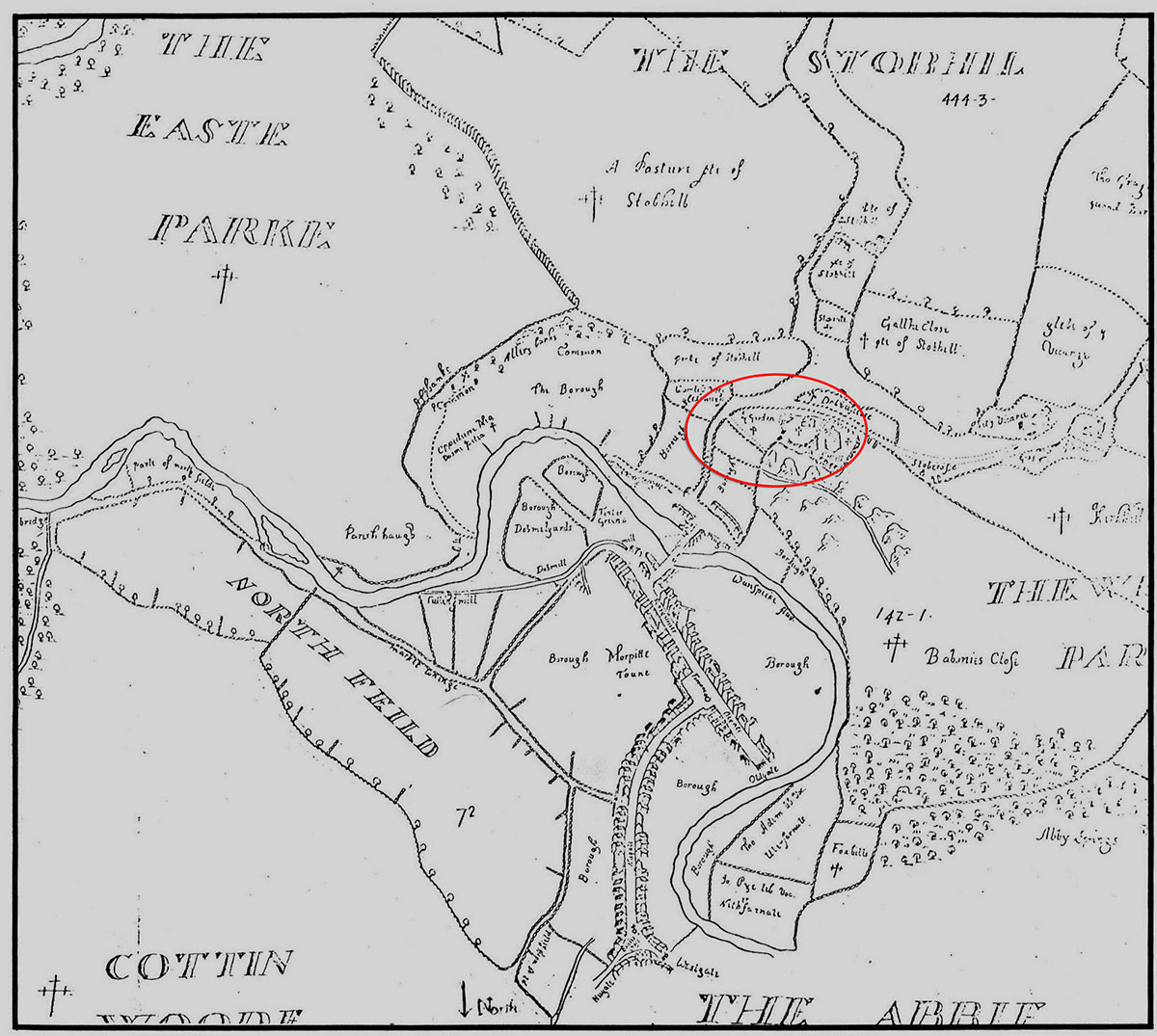

A near contemporary view of Durham

In 1650 Durham was only a small town. With the arrival of the Scottish prisoners from Dunbar its population doubled overnight. Inside the cathedral, conditions were cramped and disease spread rapidly. Sick prisoners were led away to the castle. Sir Arthur Hesilrige, the governor of the northern counties was charged with their care. He claimed that these men were decently fed and nursed, but within only 50 days 1,600 men were dead. Perhaps, after a lengthy period of starvation and hardship, the prisoners’ metabolism may have been unable to process food and nutrients, so even attempts to feed the prisoners may have precipitated death. Back in Scotland, sizeable contributions were raised by local congregations for ‘the sad condition of our prisoners in England through famine and nakedness’.

For more information, navigate using the map and click on the points shown to reveal more about their imprisonment.